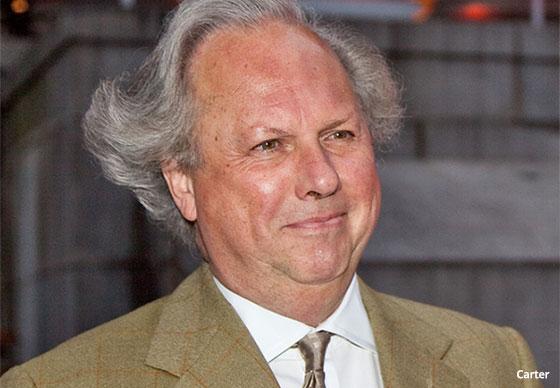

Former Vanity Fair

editor Graydon Carter has a guest column in The Hollywood Reporter’s ninth

annual New York issue that reflects on his decades-long career in “magazine city” and looks ahead to his next project.

Stale eulogies for the bygone glory days of magazines are

everywhere, but at least Carter provides some healthy perspective about the publishing industry’s transformation into the digital era.

Google, Facebook and Amazon may be gobbling up

digital ad dollars that would have gone to print ads 20 years ago, but publishers can still carve out time in the limited attention span of readers with compelling journalism.

Carter's

look-back describes a media world that is completely alien to anyone under age 40, when magazine publishers like Time and Newsweek projected power with landmark buildings and courted

advertising-agency account executives with unavoidable billboards in Grand Central station.

advertisement

advertisement

Time, where Carter worked in the 1970s, lavished its employees with every possible

service.

“Nurses. Doctors. Shrinks. And expense accounts! For my first five years in New York, I never even turned on my stove. Time paid for everything,” Carter

writes.

The first time I heard of Carter was in the pages of Spy, the satirical magazine he cofounded with Kurt Andersen and Tom Phillips in 1986. I adored that magazine — and

was glad to see Google Books had put much of its archive online. My collection of back issues didn't survive my move from college into the working world.

The magazine skewered anyone with an

air of pretense, including insufferable celebrities, arrogant media moguls and a megalomaniac real-estate developer from Queens named Donald Trump. Spy was the perfect complement to Tom

Wolfe’s “Bonfire of the Vanities” in caricaturing New York City's excesses in the 1980s.

That’s why it was so disappointing to see Carter end up as the editor

of Vanity Fair, replacing Tina Brown when she moved over to edit The New Yorker. Vanity Fair was everything Spy was not: sincere, establishment, humorless, boring. Carter

was just another social climber like Becky Sharp, the anti-heroine of novelist William Makepeace Thackeray's Vanity Fair.

But for Carter, it was great. He’d made it to the

top of the media establishment with a hefty salary and plenty of perks. Nothing wrong with that.

“I was doubly blessed to work for Condé Nast during its glory years, the '90s and

early aughts,” he writes. “During those two decades, magazines — the good ones — were thick with advertising pages and awash with the resulting profits.”

The

financial crisis of 2008, when my former workplace Lehman Bros. collapsed in the biggest bankruptcy of all time, ushered in a dismal era for publishers. Ad spending eventually recovered, but a new

crop of social-media companies and digital publishers that created iPhone-ready content were the key beneficiaries.

“Why advertisers ditched the glory of full-page print ads for the

putative advantages of mythical pinpoint placement offered by Facebook and Google is a mystery to me,” Carter writes, bemoaning how programmatic ads are wasted.

I haven't seen any

reporting to indicate that Condé Nast, faced with mounting losses, fired Carter to save a few bucks. But it would make sense. The reported disparity between his salary and that of successor Radhika Jones as editor of Vanity

Fair indicates the job title had depreciated.

While living in Provence after he left Vanity Fair, Carter concocted an idea for his next project, a digital newsletter called Airmail. It would boast an international

outlook and be easy to read on a mobile device or laptop. He says that if Spy were started today, it would be a digital publication unencumbered by printing and mailing costs.

I like

the idea of any publication with a more international scope, given the provincial mindset that pervades every major U.S. media outlet. The endless hours of navel-gazing over the 2016 election is

tiresome, and leaves Americans much less informed about the world.

Unfortunately, The Hollywood Reporter's New York issue also reveres these media elites with a disappointing list of "the 35 most powerful people in New York media."

Where is Spy

magazine when you need a good bonfire of the vanities? No one in the The Hollywood Reporter's list is more powerful than their media platform.

In 1995, technology author Nicholas

Negroponte wrote a book called “Being Digital” that discussed how the internet was going to transform media delivery, including text, video and music. "Content is king" was the message,

which still resonates today. Tech and telecom giants like AT&T, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Netflix, T-Mobile, Verizon and Google’s YouTube are spending billions on professionally produced

content to fill their digital pipelines.

Carter has similar thoughts about the physical transformation of media distribution — and the need for quality content.

“In the

magazine world, the physical properties are … shrinking or disappearing altogether,” Carter writes. “But the spirit and the journalism they provided are still available and in ample

supply online. It just takes a bit of looking."