Consumers Can't Tell Native Ads From Editorial Content

- by Erik Sass @eriksass1, December 31, 2015

Consumers have difficulty distinguishing between native advertising and editorial content, according to a new study by researchers at Grady College in Georgia, published in the December issue of the Journal of

Advertising.

Consumers have difficulty distinguishing between native advertising and editorial content, according to a new study by researchers at Grady College in Georgia, published in the December issue of the Journal of

Advertising.

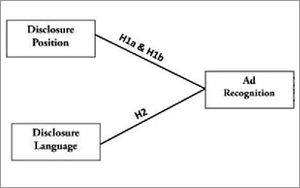

The study, titled “Going Native: Effects of Disclosure Position and Language on the Recognition and Evaluation of Online Native Advertising,” investigated how consumers react to the size and placement of native ad disclosure statements in online news articles.

In the first experiment, the researchers asked subjects to read online content with two stories, one editorial and one presenting native advertising. They displayed 12 different versions of the ad, with varying types of disclosure labels (“advertising,” “sponsored by,” “brand voice,” and “presented by”), as well as different positions for the disclosure label including at the top, middle, and bottom of the page.

advertisement

advertisement

The subjects were made to read the native ad first, followed by the real news story, then asked to distinguish which was which.

Overall, only 17 out of 242 subjects -- under 8% -- were able to identify native advertising as a paid marketing message in this experiment. The experiment also revealed that consumers are seven times more likely to identify paid content as a native ad when it is marked with terms like “advertising or “sponsored content” than if it carries terms like “brand voice” or “presented by.”

In the second experiment, the researchers used eye-tracking technology to determine the most visible positions for placement of disclosure labels in articles. Here the researchers found that placement in the middle of the page was more than twice as visible as placement at the top of the page, as 90% of subjects saw the former compared to just 40% of the latter.

Some 60% noticed the label at the bottom of the page. But even when they noticed the disclosures, subjects didn’t necessarily make the connection. Just 18.3% identified native ads as paid messages in the second experiment.

These findings should come as no surprise, considering that native advertising is intentionally presented in a format that resembles surrounding editorial content -- but they have particular relevance in light of the Federal Trade Commission’s recent unveiling of new standards for native ads, intended to prevent advertisers from deceiving consumers.

Last week, the FTC released guidance warning that digital native ads that appear in news feeds of publishers' sites, social media posts, search results and email potentially can be deceptive, unless advertisers clearly disclose that the ads are, in fact, ads. The new guidance directs companies to label native ads that potentially could be mistaken for editorial content with terms like “advertisement,” “paid advertisement,” or “sponsored advertising content.”

The FTC specifically criticized labels like “promoted” or “promoted stories,” stating that those terms “are at best ambiguous and potentially could mislead consumers that advertising content is endorsed by a publisher site.”

The agency added that even terms like “promoted by,” followed by the name of the advertiser, could be misinterpreted “to mean that a sponsoring advertiser funded or ‘underwrote’ but did not create or influence the content.”

This utter foolishness grows more idiotic by the day.

Dear Mr. Einstein, May I have a clarification, please. I'm not sure what is the "utter foolishness" to which you're referring. Refers to what? Thank you.

Native ads are typically anything but "native." They were created to deceive the audience into reading content that they otherwise would not read and "sponsored" content is no different. The last two paragraphs of this article hit the nail on the head. If you have to dupe the consumer to learn about your product or service, it speaks volumes of your lack of creativity. Ultimately, it hurts the publisher as well. If consumers don't trust the presentation of your content, they'll look for a more trustworthy source.

@Steven - the foolishness is that we spend so much time debating such a lousy advertising option.

The time will come, probably faster than later, that 'native' ads will ruin the engagement experience for web sites or other platforms.. Marketers constantly believe that the audience, be it readers or clients or consumers, is stupid and ignorant. People will learn how to spot advertising camouflaged as editorial and avoid it.

There was a time, back in the 90’s, when content created by advertisers was marked as sponsored content, and which also went through editorial rigor to be sure it was something the publishers would have created themselves. I remember created content for Midas about alignments, brakes and so forth. The consideration by the publishers was if the content really added value.

It seems that as technology made it easier to embed content and add inline links publishers allowed advertisers to indulge in their worst habits of laziness. What is somewhat new in the FTC guidelines is that publishers might be held accountable for the deception as well, where historically that burden fell almost exclusively on the advertisers. Not often said, but the FTC is simply forcing advertisers and publishers to do what they should be doing for a good user experience.

Native ads are deceptive on purpose. Publishers and advertisers know it. They know that to the consumer "Sponsored Content" triggers memories of news programs or other TV or radio shows that were "sponsored by" a national trusted brand and DID NOT control the content of the broadcast. They assume that a sponsor helped support the indepdent reporting of content to follow, writting or video.

If advertisers were not trying to trick readers, they would have not problem saying "PAID ADVERTISEMENT" over the content. They also would not take pains to make the content look like the read editorial content of the site, publication or program... which they almost always do.

The FTC has every right to make sure ALL native advertising is slapped with a VERY clear label so the public understands what they are seeing. Any attempt to stop that is nothing more than a shell game to trick readers and line the pockets of publishers.