Eye Tracker Finds Which Ads Actually Stick, Pushes 'Cost-Per-Visual' As New Madison Avenue Currency

- by Joe Mandese @mp_joemandese, April 22, 2013

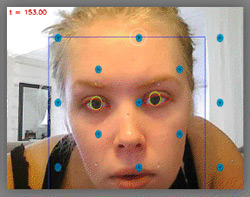

Even as Madison Avenue pushes to raise the bar for ad exposure from an “opportunity to see” to a “likelihood to see,” a promising new research technology has emerged that could raise it even further to, well, actually seen. The new research, which is based on state-of-the-art eye-tracking technology, uses consumers' own eye movements to verify what ads they have looked at.

While eye-tracking technology has been around for years, what makes the new system -- dubbed Sticky -- so powerful is that it doesn’t apply it in a laboratory or a resting facility, but in the real world, in real-time, while people are exposed to ads online.

“Fifty percent of all ad impressions are never seen,” says Jeff Bander, president of Sticky, who recently won the Advertising Research Foundation’s “Great Mind Award” for helping to develop the innovative media tracking technology. That percentage, he notes, is the same as the oft-quoted John Wanamaker line: "Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted. The trouble is, I don't know which half."

“Now,” says Bander, “we know which half.”

Utilizing the webcams built into their own computers and handheld devices, Bander says Sticky has already tracked ads actually seen, or not, among 350,000 consumers. That’s 700,000 eyeballs, more or less, creating a new form of media currency that some of the biggest advertisers in the world have already begun to use. Among Sticky’s biggest customers is Procter & Gamble.

How Sticky might play into media negotiations isn’t exactly clear, but it comes at a time when Madison Avenue is pushing the online industry to adopt a new standard of “viewability” for advertising exposure, meaning an ad has to be viewable on a consumer’s screen -- not “below-the-fold” -- for at least one second to be credited as an ad exposure. Fifty percent of impressions are never seen.

“Viewability is nice, but viewability just means that an ad is within the viewable area of a screen,” notes Bander, adding: “It doesn’t mean a consumer is actually looking at your ad.”

Citing estimates from the Interactive Advertising Bureau that as much as 30% of online ads run outside the viewable area of a consumer’s screen, Bander says viewability is a good first step, but that the only way to know if someone has actually seen an ad is to track their eye movements.

Sticky was recently re-branded from its original corporate name, Eyetrackshop, to evoke the connotation that only the ads your eyes stick to are the ones advertisers should pay for. Bander says that logic evolved from some early beta work Sticky did with P&G, which wanted to know which of its ads were seen or not seen, in order to develop a “real CPM,” or cost-per-thousand for the money it spends to reach consumers.

“Their question basically caused us to reinvent our model,” recalls Bander, who says Sticky has refined the notion of a CPM by developing a CPV, or cost-per-visual, which is the actual dollar cost of reaching 1,000 consumers -- or 2,000 consumer eyeballs.

If this gets widely adopted (and I hope it does), it may simply result in a net increase in rates for "eyeballed ads"... so advertisers end up paying more, but for less impressions. It could put a lot of negative pricing pressure on networks that do not adopt the system, such as (potentially) many of the smaller ad networks.

This is a very interesting proposition. The publisher has a website which an advertiser 'rents' space on. While the publisher has control over the rate it has no control over the creative content of the ad. The basic proposition that no matter how crap an online ad is it should pay the say CPM as the best online ad is pretty flawed. The rush for publishers to vet creative content will be on so that that they don't get fleeced by lazy digital agencies and marketers content with sub-par unengaging marketing messages.

@Chris Clouten,

You can relax. The eye-tracking studies are only done with participating consumers. See this: http://eyetrackshop.com/survey-legal-info-and-privacy-policy

Great article. How does Sticky differ from Gaze Hawk, which Facebook bought?

Nicely said John Grono. So the drawing of an ugly girl with a siren flashing on her head will indicate that section of the page is worth more than another. It seems the best way to test it might be to have the same ads (or slightly different versions because of size) in all of the available slots and develop a scoring system. Daniel Starch used to do it for magazines and Newspapers through focus groups.

Chris,

You must have been at our meetings, this is exactly what we are doing.

Cheers,

Jeff

Chris, not to get all gender political on you, but I was happily reading the comments until I read the phrase, "ugly girl with a siren on her head." As a woman who has encountered and witnessed stereotyping (from both genders) I would encourage you to think about using terms like ugly girl so blithely.

Creepy creepy creepy creepy creepy creepy creeypy.............

Very interesting, Jeff. Do you plan to issue any general findings---type of ad, format, video vs display, etc. soon? Also, have you developed your own definition of when an ad is "seen"----like eyes must be on a 15-sec. video ad for all 15 seconds?---eyes must stop for at least three seconds on a static display ad, etc.?