Update On Advertising's 'Subliminal Seduction'

- by Todd Wasserman , March 28, 2022

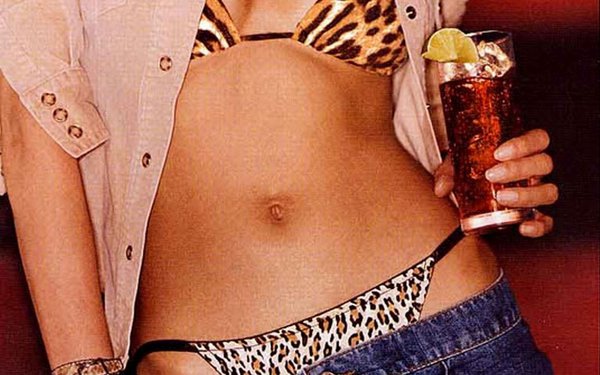

Advertising has long been linked to sex. A 1974 book called “Subliminal Seduction” documented how advertisers shoehorned the word “sex” into advertising images. Some recent ads, like Burger King’s 2009 ad for its seven-inch burger, featuring a woman about to take a bite with the caption “It’ll blow your mind away,” leave little doubt about how marketers use sex to sell products.

A Washington State University study recently made the case that alcohol advertising featuring objectified women encouraged male and some female students to manipulate others for sex.

advertisement

advertisement

“This study showed that the way that we interpret the alcohol ads can affect what we do in our romantic and sexual lives, because … alcohol [advertisers] connect their products to sexual activity or romantic appeal,” Stacey Hust, associate dean of faculty affairs and college operations at Washington State University, told Marketing Daily.

Hust said the study showed that those with greater stereotypical beliefs about the sexes were more likely to sexually coerce people after seeing the ads.

“It’s based on how they interpret those advertisements,” Hust said, adding that if the ads sparked a desire to be like the people in the ads or if they came into the ads with greater gender-stereotypical beliefs, “then they’re more likely to report intentions to sexually coerce individuals after seeing advertisements.”

Hust said there’s not a direct causal link between seeing the ads and sexually coercing people. “It's not like if you see an alcohol ad, you're going to go out and coerce somebody,” she said. But the ads alter the viewer’s perceptions, which causes them to act differently than they likely would have if they hadn’t seen the ad.

Hust said additional research confirms that gender stereotypes are predictors of sexual coercion. “So beliefs that women are passive sexual gatekeepers, and that men need to be sexual aggressors, are associated with greater intention to sexually coerce,” she said.

The research found that the alcohol ads didn’t have an effect on all the study participants’ sexual coercion intentions. But the ads had a negative influence when the viewer perceived women through a view informed by gender stereotypes or when the viewer was a woman who had a wishful identification with the depicted models.

The problem is bigger than the advertising, Hust said. She noted that education, particularly early education about advertising, is the key to undermining its efficacy.